Think about how you know him. He’s subtly omnipresent to the point of existing in our collective unconsciousness the way founding fathers or historical figures are- he’s John Wilkes Booth, existing to be the assassin in Abraham Lincoln’s story. He’s Herbert Morrison, necessary to breathlessly describe the Hindenburg Disaster, so that it better becomes a repeated soundbite in future film montages. He has no narrative arc of his own, serving only to further the narrative of others.

He has no individual personality or inner life except to exist primarily to, at times, prompt or discourage Stan Lee. His entire history up to serving this purpose is meaningless and unquestioned with minimal exceptions. Yet he remains absolutely necessary for Lee- and Marvel’s- grand and repeated saga to exist and to continue to exist in the next century. He is Martin Goodman, the founder and publisher (and relative) of Stan Lee.

So many warm and charming retellings of Stan Lee’s struggles and sacrifices to bring Marvel’s characters and universe into being have to include this man in order for them to not just exist, but for the story to work. So, he exists as an important and necessary catalyst for the all-important and inescapable origin story of Stan Lee and modern Marvel as we know it- without him as a foil, these oft-repeated tales of Stan’s struggles to birth a new form of storytelling, a new mythology- cannot hold up, cannot stay there in the grand narrative of pop culture or history. Without Martin Goodman the foil, Stan’s Great American Story will fall to pieces.

Then, consider: Nearly everything we know about Martin Goodman comes entirely from Stan Lee’s anecdotes.

The most biographical information of Goodman’s life that Marvel has ever put forward in print is that he spent a great part of the depression hoboing train-to-train around the country, a fascinating aspect of any self-made millionaire’s life that is frustratingly and bizarrely never followed up on.

Again, Goodman serves a necessary purpose as a narrative crutch, a MacGuffin- there has never been any interest in who he may have been, what he may have stood for, so pivotal is he, so perfect in casting as the bane of Stan Lee’s creative genius. The famous story of Lee “doing it his way” remains so intoxicating to fans and journalists alike, that any wavering from that narrative is testament to treason in the comic book community, a sure sign of being a “Stan hater” and close-minded zealot that questioning anything, or, worse- bringing up factual evidence- provokes nothing but willful ignorance.

With that being said, we are today going to examine a bit deeper the genuinely interesting and complex man that was Martin Goodman- and see that much of what was ascribed as a historical figure was perhaps both unfair and some of it almost blatantly untrue.

This is not to defend or excuse Goodman’s business practices or rationalize his lack of handling over creator rights. This is simply to provide more context to a man who exists as a cipher almost, a character in a play that functions solely to provoke a monologue from the lead character. Looking at him as a more complete individual also casts many of the actions attributed to him in a more questionable light. Goodman- per Stan Lee- has been cast as stodgy, cheap, conservative and close-minded both creatively and financially, endlessly bemused and prone to running off to Florida when it was time to fire people. Perhaps it really is entirely true. Let’s look at some things that, while lesser known, are still known to be true about Martin Goodman.

Goodman was remarkably progressive for his era, or at least as any self-made millionaire publisher could be that lived and operated in the 20th century. A firm believer in the benefits of psychology, Goodman and his wife were well established in the intellectual communities of New York, donating to Jungian research and being one of the primary donors towards an alternative medicine school that sought to use Yoga as a therapeutic device for people suffering from chronic pain. Goodman’s wife Jean was a highly educated woman and patron of the arts who supported alternative education and feminist outreach.

Martin and Jean counted the highly influential couple Kenneth and Mamie Clark among their friends; the married couple were prominent psychologists who were highly active in the Civil Rights movement. The Clarks and the Goodmans regularly dined together at both the Goodman household and the Clark’s home in Harlem. Martin Goodman was very ahead of his time in regards to racial equality which doesn’t necessarily mean he deserves credit per se- but his apparent lack of concern over dining with Black friends and his pride in having them as friends during a time of segregation and Racial inequality speaks volumes to both his character and his outlook.

Goodman was also an early advocate and defender for Gay rights, shushing the use of “queer” as a derogatory term in his presence at the Atlas Seaboard offices and, as historian Patrick Ford reminded me, gladly employed Raymond Marris and Ron Whyte, both of whom were Gay, out, and who lived together.

You might be thinking that the point I’m getting to is that I believe Goodman deserves a pass due to his enlightened and quasi-bohemian lifestyle at this point, perhaps? That he’s not such a bad guy due to his progressive stance at a time when such stances weren’t. No- I included this simply because I genuinely found it both refreshing and interesting, nothing more. Now that I’ve fleshed out some partial biographical information you may not have known… let’s revisit some very familiar stories.

“He said, ‘Stan, I’m surprised at you. A hero can’t be a teenager.”- Stan Lee

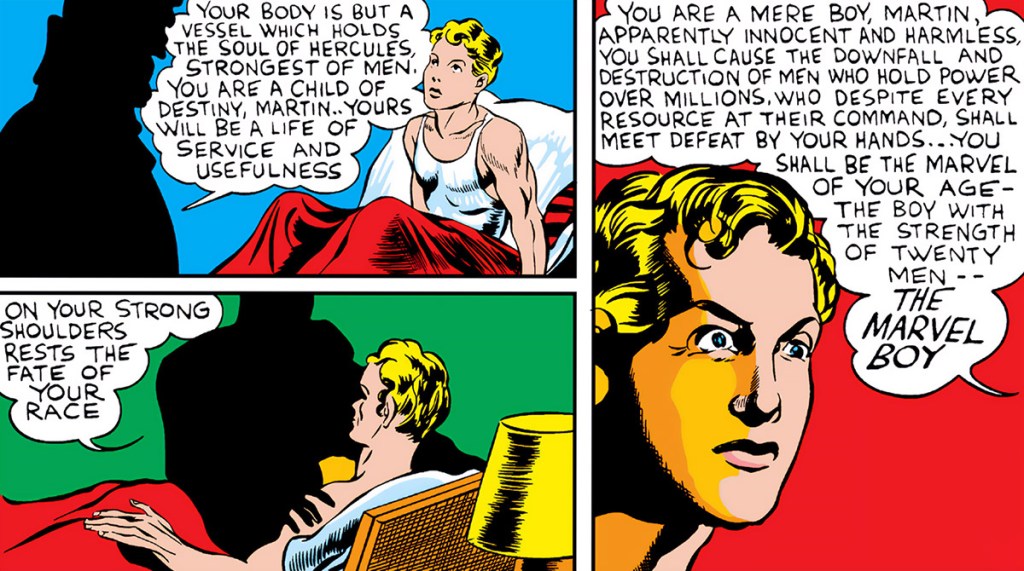

One of the crucial and history making components of the Spider-Man story in Martin Goodman’s apparent rejection of Spider-Man is that he simply couldn’t function since he wasn’t an adult. This is something rarely questioned or dwelled upon which I find interesting, considering the fact that Goodman regularly published teenaged heroes– whether in anthology titles or their own solo series.

Terry Vance. Marvel Boy of the Forties and Marvel Boy of the Fifties. The Young Allies. You might argue this isn’t a huge list, but the fact remains that Goodman certainly didn’t shy upon publishing teenaged characters in the past. I will play Devil’s Advocate and admit that it’s possible that Goodman did say this to Lee in response to possible poor sales of those earlier characters- I generally tend to shy away from speculative theories, you know- but the fact of the matter is that this seems much more a case of ol’ Stan inventing and cultivating an entertaining tale for the collected journalists that visited with him over the years. Otherwise, Goodman’s philosophy on teen heroes is a blatant contradiction of Lee’s apparent recollection.

Goodman’s portrayals in Lee biographies and various Marvel history tomes range from cocky bemusement to outright dictator-esque behavior; he at times is either obsessed with other comic publisher’s sales or is outright oblivious of trends and what the kids want. One thing notable is that the outright top seller of the entire Golden Age- the most profitable time in comic book history up to that point, and one that Goodman would have been well aware of- was Fawcett’s Captain Marvel. And, as I’m sure anyone reading this knows, the alluring concept of Captain Marvel was that a young teen said a magic word to become the adult hero. It was intoxicating for children, and at one point, Captain Marvel Adventures sold 14 million copies in 1944. It’s 1.5 million per issue average in the Forties made it one of the first comic books to go biweekly. Would Goodman- a prolific publisher himself- been unaware of this?? It defies logic. But Lee anecdotes often do.

This anecdote also supposes that Goodman may have had a strong outlook on what constituted a super-hero when Lee, at times, said that Goodman “didn’t have the first idea” about what a super-hero should be- these statements again contradict and are rendered suspect just by the publishing history of Martin Goodman. So is it outside the line of reasoning to think that- just maybe- Martin Goodman never said this in regards to Spider-Man? Again, I repeat: Nearly everything we know about Martin Goodman comes from Stan Lee’s anecdotes.

Remember the lack of logic in Lee’s Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos tale. Goodman, a notorious penny pincher and cheapskate not prone to experimentation or risks whatsoever per Lee and various comic experts, tells Lee that the recent success of the Marvel line must be the titles. Lee responds that it’s the writing and, to prove it (!), he’ll come up with a series that has the worst title he can think of and prove it can sell. Goodman, a conservative with finances who studies the market and the competition, accepts this bet (!!) for the sole purpose of “finally proving” Lee wrong, since this is apparently an ongoing and verbalized issue of Goodman’s that Lee is seemingly aware of. Think about that. Think about how blatantly false and nonsensical that story is and how it cannot hold up in the face of logic and recorded history. And yet people accept this story, even when many of the contradictions about Goodman have been regularly provided by Lee himself.

(Lee also claimed at times that his motivation for Sgt. Fury was to be contradictory, the same reasoning he used for seemingly inventing Tony Stark at a time when college kids apparently hated industrialists, but that’s another conversation.)

“And you say you want him to have problems? Don’t you know what a superhero is?’ He was the boss, and I couldn’t put ‘Spider-Man’ out.” – Stan Lee

“I snuck him in the last issue… I thought, well that might be the end of my job!” – Stan Lee

I’m willing to concede that some of what Lee said was intended with a tongue-in-cheek tone but the point remains that journalists have taken him literally in regard to the potential loss of his job due to defying Goodman. This therefore becomes a significant part of the narrative and also is unfair to Goodman.

Another unintended consequence of lazy research is the possibility of Lee sneaking in a feature without Goodman being aware of it. This was simply not possible as Lee even had a second cover commissioned and paid for- or was it possible, depending on which continuity Lee is referencing? Was this the narrative of Goodman as aloof and barely present or the narrative of Goodman as constantly involved and vetoing ideas? Again, Lee’s claims do not stand up not just to scrutiny but also to basic questioning.

So, Goodman’s history of publishing teen heroes semi regularly, or even occasionally should be held up as a defense towards the popular and repeated claim against him about saying teenagers can’t be heroes. Goodman’s history of keeping an eye and- per Lee- approving every cover should be held up as a defense towards the claims of Lee “sneaking in” a feature without Goodman’s knowledge and then suggesting that Lee was in danger of being fired once Goodman found out. It’s simply an unfair mythology.

One last thing. In 2010, I’d been regularly corresponding with Alan Kupperberg whose sense of humor and love of the comics industry I found quite infectious. He was gregarious and warm with me, and I was quite curious about the Goodman family, of which not much had been written of, so asked him about anything specific he might share. He had already written and drawn an amusing incident with Goodman for his brilliant Sequentially Illustrated series. Sorry, Jeff Rovin.

Kupperberg was involved with Goodman’s second comics company Atlas-Seaboard (itself unfairly and easily maligned as just an “act of revenge” by many) and had, by his admission, “only two actual” conversations with Goodman when I’d started inquiring more about his interactions and observations there. Kupperberg told me something in passing I found quite compelling.

In 1971, Amazing Spider-Man famously published three issues sans the famous seal of the Comics Code Authority after Lee was asked by a representative of the National Institute of Mental Health to do a story-arc denouncing the use of narcotics. Lee bravely decided to publish them without the approval of the CCA- it’s worth noting that Lee does credit Goodman as supporting this decision, prominently declaring that he was “proud” of him in a 2003 documentary on the History Channel- and history was made as well as the beginning of a much needed evolution in the CCA itself.

Kupperberg claimed that Martin Goodman himself was the one who told Lee they’d simply run the issues without submission when Lee was weighing the possibilities and logistics of even attempting such a story.

I remarked that Lee not only got credit for this but was quite outspoken about it. Kupperberg remarked that Goodman was going to be indifferent to any credit for, as his role as publisher, this was not the kind of decision he’d think warranted being singled out for. It’s also worth noting that what we know of Goodman supports his taking such a revolutionary stance, as he already a believer in alternate medicine by the late Sixties and was already outspoken and supportive of therapies that didn’t involve pharmaceuticals in general, verbally telling staff they were allowed time off if they had a therapist they saw and once making a grumpy comment about an employee prescribed medication for anxiety- possibly Larry Lieber, whose therapist Goodman both suggested and paid for.

(This is supported by an interview with Gary Friedrich in which he said Goodman hired him back at Marvel after Friedrich took Lee’s advice to lie about starting therapy with a psychiatrist as well as Lieber speaking about his own anxiety issues in the same magazine.)

This becomes more probable as a possibility when you now look at Goodman’s life which was rich and diverse, however he was described by Lee. And this is not to take credit away from Lee- but the possibility that it was Goodman who made both the suggestion and decision to break away from the Comics Code Authority does have credibility. For what it’s worth (because I asked), Kupperberg told me that Larry Lieber was the one who shared this knowledge with him and not as a dig at his famous older brother, but with a tone of clarification, as he put it.

Gary Friedrich said that Martin Goodman was the “best boss he’d ever had” and, far from being an iron fisted tyrant, was “liberal” and didn’t care how you spent your time “as long as your work got done.” Herb Trimpe warmly spoke of Goodman once, without question, forwarding him $800 that Trimpe could pay back by having interest free deductions taken out of his paycheck at a time when Trimpe was having serious family issues. Trimpe spoke of the “family environment” atmosphere he found at Marvel during the Goodman era.

Other staffers have described Goodman as aloof, quiet, napping in his office, obsessed with Scrabble, but the majority of truly negative anecdotes we hear all stem from the same source. Are these anecdotes I just shared from Friedrich and Trimpe the gestures of a man constantly insulting his staff, questioning the value of paying his staff, and threatening to fire his staff on a whim, as Lee often reported he did? With Lee the lone barrier between Goodman and the freelancers, Lee the sole defender of worker’s rights?

Above all, I hope that a richer image of Martin Goodman as an individual more than a prop has emerged from this. Regardless of his faults, he has been used as a character in a false narrative that has persevered for decades. We should assign both credit and blame accordingly- and not have to make up either in order to further ourselves.

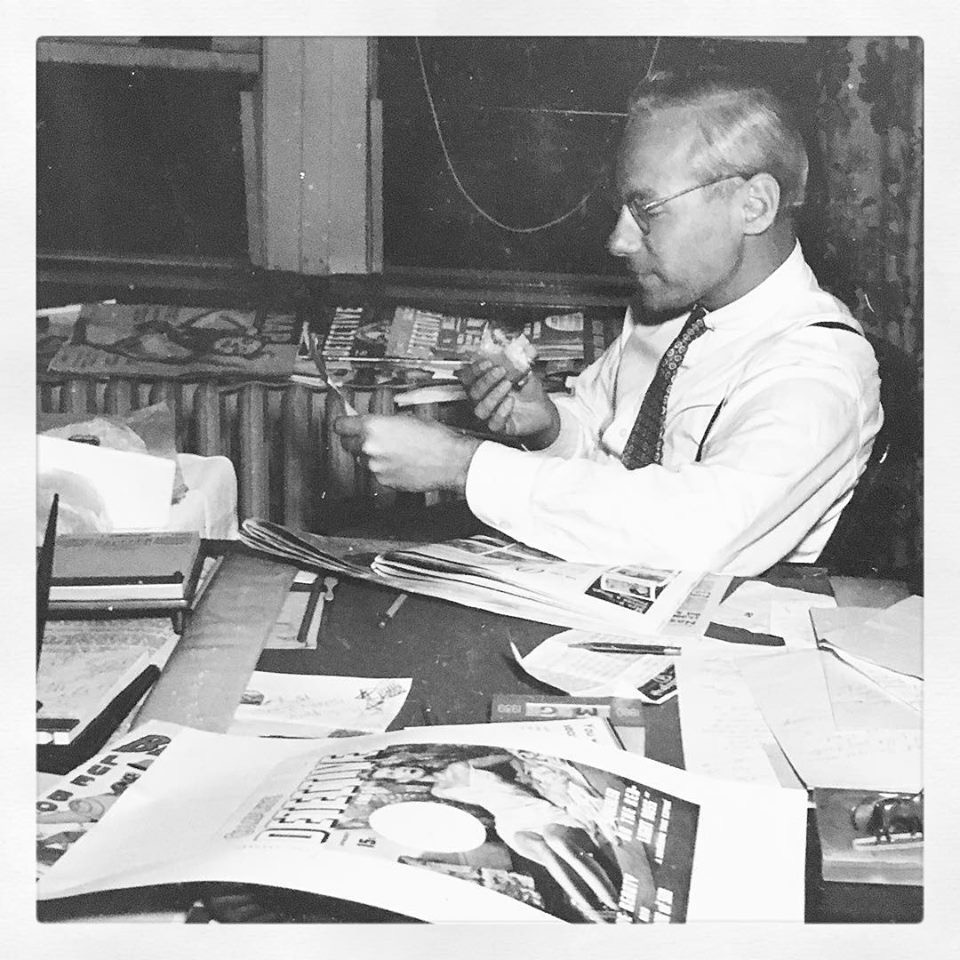

The first three photographs of Martin Goodman were family photographs shared courtesy of the Goodman family. My thanks to the late and great Alan Kupperberg, Patrick Ford, JL Mast, Michael Hill, Michael J Vassallo, Jon B Cooke, and PulpArtists.com.

Nice piece!

Of course, there are digs at Goodman from sources other than Lee—Kirby and Ditko for two.

A few more quibbles: It’s an ancient story that between his memory, ego and contractual obligations to lie about who created what, Lee is beyond a simply unreliable source. It’s like panning for gold to figure out how much truth is in any claim.

As to Marvel Boy being any sort of proof that Goodman liked teen heroes: The character was a) the only teen hero from Goodman at the time and b) was a commercial failure. So ca Amazing Fantasy 15, maybe Goodman was gun shy about a teen hero. Since we’re speculating.

As for Atlas 2.0, after the first two issues or so, nearly all the color books turned to dreck, in huge part because Atlas was, like Marvel in the 60s, not all that creator friendly. No dis to Trimpe, but better a fair wage than having to rely on the boss for a loan.

Respect to you, anonymous blog writer, for your efforts to cut through the BS and legends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quibble away, I welcome all the good points and even criticisms. Thanks!

LikeLike