There are some things I need to say at the offset of this review, if you don’t mind.

‘Super Visible: The Story of The Women of Marvel Comics’, written by Margaret Stohl, with Jeanine Schaefer and Judith Stephens, was published- notably, by Marvel *(see below)- in June of 2025. I apologize that it’s taken me this long to get to reviewing it properly.

This is an important book; this is a necessary book in the overall documented history of the comic book industry and its contributors, but it’s also a flawed book and, in the interest of complete fairness, I have to call out a few key errors and questionable decisions- purely related to factual things, ‘natch, and not because it’s coming from women authors about women creators- I believe the medium needs such things, trust me.

But even these writers- three of them, at that- well, they fucked a few things up, sad to say, and it falls to your humble and gregarious host to point out those things, including one that I find immensely disappointing from these ladies. We’ll get to that.

I have to note that, in the middle of writing and compiling this, the horrific and beyond senseless murder of Renee Good occurred, shot in the face by an ICE Agent. I was devastated by this but also anguished that the ICE Agent, after discharging his weapon, mutters “fucking bitch” with absolutely no sense of empathy or remorse for what he’d just done.

It was a manifestation of the entitled white male rage so many men have in this country; they’re triggered when women laugh, they’re furious when women aren’t interested in them. It magnified just how dangerous sexism and male dominance is in this country, on this planet.

Men resent women and their agency and their power. It can’t be denied and I, personally, won’t let another man deny it. But it added a weight to reading this book, which, while valuable, is contrasted by terribly hasty and poorly thought errors (again, about factual and documented comic book matters which are frivolous compared to the real world plight of women) and meaningful first-hand accounts from a number of brilliant, talented women about their struggles and successes in a largely male-dominated industry producing for a historically male-dominated audience.

There’s also a prevailing and ever-present glorification of modern Marvel at all times, which leads me to suspect that the House of (other people’s) Ideas loomed large over the trajectory of this book. But! Let’s get into it, o frantic ones.*(note: I wrote that before I checked the publishing credits in the beginning of the book- rookie mistake!)

At the offset, this is gorgeously designed with a treasure trove of great photographs, and, while I’d seen several of them before, they previously appeared in damaged goods fanzine Alter Ego so, all the better to have them in a better, more accessible publication.

“The way it feels for us, and for other women and nonbinary creators. Which isn’t a single story, and isn’t the same story, and isn’t the story a white male Marvel Comics creator might tell.” – Prologue, XIX

Pg. 5: “At the time [reading comics as a teenager], I didn’t notice it. It went over my head,” said Trina Robbins, a writer who worked at Marvel in the 1980s, and a comics historian who, before her passing in 2024, had written extensively about the history of women in comics. “But now, of course, more recently, I look back and I see, ‘Oh my God, she’s actually invisible. Typical. And it was true; women were invisible in comics.” – Trina Robbins

Some historians have suggested that the Invisible Woman was latently inspired by the memory of Invisible Scarlet O’Neil, an influential and popular superpowered character that appeared in comic strips and comic books of the Forties and Fifties; Robbin’s observation is much more poignant and telling.

Pg. 10: “But it was only whenever the stakes were lowest that women seemed to have the best access. For many women, the 1960s seemed to usher in a time of at least measured opportunity in New York professional circles. And a small industry like comics- supported by a fledgling, insular “nerd culture,” where everyone already knew everyone- was an easier entry point for a career-minded wife or girlfriend than more established Madison Avenue vocations like advertising or book publishing.”

The authors make a valid point that a woman in her twenties during the Sixties would have been much more likely to have grown up reading comics than they would in modern times.

There are a few things I feel are a slightly too pop culture-ish in the writing, such as adding “Mad Men, Marvel-style” to compliment an anecdote about the women going out for drinks at a nearby bar, but otherwise, these accounts are very valuable and help paint a deeper picture of how Marvel worked during this seminal time.

Pg. 15: “There was also the fan mail, or Stan Mail, as the girls called it. “I know one of the things I had to do was a passable facsimile Stan signature, a very bold S-T-A-N,” recalled Jean Thomas. “Never on anybody’s checks, just on postcards that went to kids.”

Someone needs to tell the aging Merry Marvel Marching members that those treasured items in their display case aren’t autographed by ‘The Man’ at all…! Though, Jean Thomas has been experiencing a bit of a resurgence since John Cimino got her retroactive co-creator credit on Werewolf by Night, so maybe it’s still worth something. Someone check on Barry Pearl for me though, just in case.

Pg. 16: “Uncredited, women most often helped write the Bullpen Bulletin, a one-page newsletter that ran each month in the back of every issue. “Stan would do his little ‘Stan’s Soapbox,'” [Linda] Fite said of the publisher’s personal column. “But alongside there would be the Bullpen Bulletin– who was doing what, what was coming up- because Stan very wisely personalized the entire creative team. I’d copyedit the Bulletin and sometimes help Stan. I came up with some Latin expressions for him because I’d studied it in high school.”

“And so, a circled bit on Linda’s resume- the fact that she had the ability to type- soon meant she was writing in Stan’s voice to fans around the world.”

“Said Jean Thomas with a little smile, “It took a village to create Stan.”

Let me also point out that I had absolutely no intent whatsoever to use this book and tie it to other things I’ve discussed here in the past; doing so would be a disservice to the entire point of this book and I recognize that. So, I am really not trying to connect some of the things shared here for any overall or underhanded purpose, but… some of this stuff… it’s… hard to not say something…

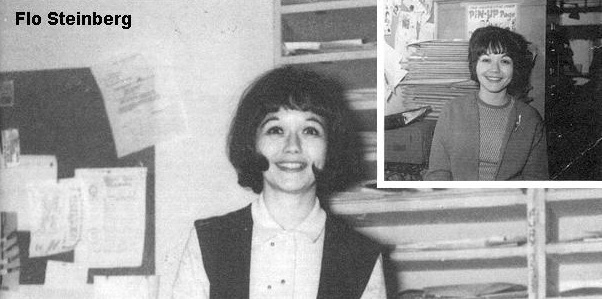

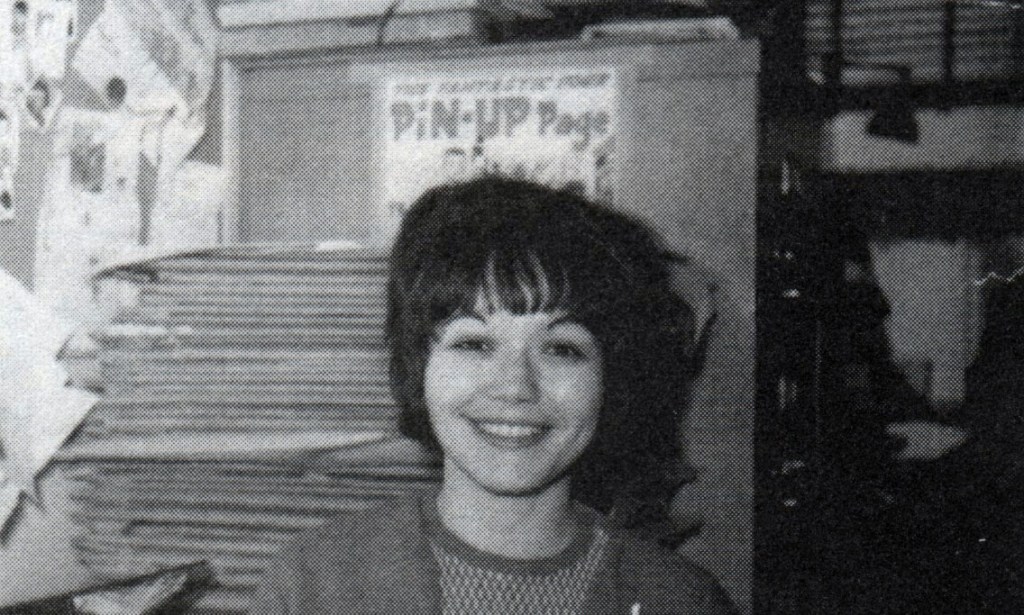

Pg. 18: “She [Flo Steinberg] handled all the letters (which she would often answer herself, writing as Stan to younger readers…”)

There exist many accounts of adults in the present whose sentimental loyalty to Stan Lee stems from receiving a personal message from him in the Sixties. Not that I think that sentiment would diminish, but I still think they should consider that they might not have gotten a message from ol’ Stan at all. I mean, me personally, I’d dig just hearing from Flo. But still.

Also, and as you’d expect, Stan the Man is given consistent credit for being a visionary architect and even “seeming to know” things that he likely did due to circumstances and time constraints. There is no person in all of comics who is projected on as much as Stan Lee and it remains true in this otherwise valuable book.

Pg. 20: “Flo was totally competent. Real smart. She was originally hired as Stan’s secretary, his personal assistant, but would become so much more than that in the office,” Linda went on. “She would manage the traffic of artwork and flow of the schedules. She took care of Stan.”

This is the first I’ve heard of Steinberg being involved in logistical duties like the traffic of artwork, though I don’t doubt it at all-, but it certainly isanother nail in the coffin about Lee being “too busy” to write scripts. (And this is what I meant when I said I didn’t start out reviewing this book to find more things to point out about Lee’s shady history.)

As I’ve written in depth here before- what was he so busy with? Sol Brodsky, per Lee’s own documented accounts, handled all the administrative and logistical work. (Well, now we must add Flo Steinberg to that list!)

Stan Lee came in three, and then two, days a week- what was he so busy doing that he relied on artists to generate plots? Linda Fite reveals more with this statement, and the fuller picture of Stan Lee’s grifting continues to grow.

The authors very briefly go into the Romance Comic boom (started by Simon & Kirby), mention Timely’s interesting GIRL COMICS (which they credit to Stan Lee trying to bring girls into different genres than Romance Comics, when some historians believe Martin Goodman directed this), through to Fredric Werthham and the Comic Code Authority, right to 1972’s female-led series of books including Night Nurse, Claws of the Cat, and Shanna The She-Devil. whew!

Pg. 23: “In what should be commemorated as a vital piece of Marvel history but has been lost in the shuffle like much of the details about women in the early Marvel era, The Claws of the Cat #1 was Marvel’s first book credited to both a female writer and illustrator…”

Pg. 25: “Carole Seuling was selected for the third book, Shanna the She-Devil. By 1971, she and Phil Seuling were separated, and she was working as a substitute teacher. “Roy [Thomas] approached me and said he wanted a jungle queen. They then left it up to me to make up the origin story.”

Not a surprise that Roy Thomas directed someone else to create the character and then come up with the story behind it. He probably feels he deserves co-creator credit on it, too. (See also: The Goodman Rule)

Pg. 25: “There’s a cynical version as well, voiced by a few women we spoke with, who had the unfortunately too-common experience of being trotted out and then tossed aside: that they “would introduce girl books… but nobody will read them because girls don’t like comics, then we’ll cancel them, but be able to say we tried.”

But the practical view of why Stan wanted to get into the women’s comics space could be as simple as this: he was a savvy businessman and saw an audience out there who wasn’t being served.”

UGH. There’s just too much of this. Admitted speculation, even when the women they spoke with of that time told them otherwise. I mean, I get it- these are all women connected with MARVEL, who have a successful podcast called Women of MARVEL. They have to sort of work extra to subtly defend Stan Lee and give Stan Lee the benefit of a doubt. In this sense, we finally have gender equality when it comes to people associated with the House of Ideas.

Pg. 30: “It was through an assignment for Esquire in 1966 that publisher Martin Goodman and Stan Lee finally noticed Marie [Severin]’s skills as an artist, offering her the opportunity to take over from Steve Ditko on the “Doctor Strange” feature in Strange Tales the following year.”

This one surprised me. Also, I really, really mean it when I tell you, I am not looking for Stan Lee related things to point out, but they keep forcing me to. The authors seem to begrudgingly credit Martin Goodman- true– but then add Stan Lee, for some reason. The story has been well repeated, and helpfully by Severin herself- Martin Goodman saw her artwork for an in-house ad and reportedly said, “Why is she doing ads? Put her on stories!”

I had read that a handful of times over the years and then found this interview excerpt where Severin says the same thing about Goodman. Why they felt the need to include Stan- who I’m sure was genuinely pleased with Severin’s work, I’m not suggesting otherwise- is baffling, and adds to the impression that they are have been dictated to only include Stan Lee in as many positive and proactively progressive things as possible.

God Loves Comics | How Marie Severin started drawing at Marvel (thank Martin Goodman). | Facebook

“She was always capable of more, but it wasn’t until the 1960s and she had been working at Marvel for a while that she was given the opportunity to draw comics herself. It wasn’t the usually canny Stan Lee who realized her talents, either; instead it was Marvel’s publisher Martin Goodman that noticed how good she was when she did some superhero drawings for Esquire and so Severin began to draw sporadically for the company.” – ‘Marie Severin’s Due’, by James Romberger, 2012

This has been commonly reiterated and repeated, even in the TwoMorrows biography of Severin, The Mirthful Mistress of Comics. Stan Lee did what Goodman told him to do- and that isn’t a slight- that’s just how it was.

“So, I went over and I got the commission, and when that came out, Mr. Goodman saw it and he told Stan, “What is she doing in the production department? Give her some art work.” – Marie Severin Interview on Sequential Tart, 2001

“In the early 1960s Marie began working for Marvel full-time, at first as production assistant to Sol Brodsky, but her duties grew after publisher Martin Goodman saw her art on a house ad.” – Nick Caputo Blog, 2017

“When Martin Goodman saw the printed version, he said, ‘She shouldn’t be doing paste-ups, she should be drawing.'”– Marie Severin Interview, The Jack Kirby Collector #18, Nov. 1997

“It was a page like that Martin Goodman saw that made him tell Stan “She should be drawing some of the comics”… Roy Thomas, 2012

Listen. If you don’t suffer from being able to remember every single thing you’ve ever read once something triggers said memory, then you don’t know what it’s like to be me! I can’t help but bring this stuff up. Send help immediately!

Pg. 31: “The office [felt] unwelcoming to women, but Marie was totally at ease in her little domain, and a decent number of the colorists were women.” -Francoise Mouly

Pg. 33: “Creator and editor Annie Nocenti admitted, “I was scared of her. She was so sardonic, funny, and deadpan. Kind of like you never knew if she was happy or not, if she was angry or not. But she was wonderful. And you know, I just completely fell in love with her.” Annie paused. “Marie really should have made it to art director.”

Why didn’t she? “Sexism.” Annie shrugged. That was comics in the 1960s.

Pg. 37: “Marvel had just expanded, and they were desperate for people who knew the business, because nobody had time to tell them what a comic book was,” said Irene Vartanoff, who started her comics career at Marvel in 1974 as then editor in chief Roy Thomas’s assistant.”

I found this statement incredibly notable, for what Vartanoff says in passing, almost casually. Marvel “had just expanded”- this alludes to Goodman having sold Marvel- and “they were desperate for people who knew the business” alludes to, I believe, the lack of people with administrative and distribution knowledge since, essentially, with the Goodman family gone, you had Stan Lee and uber-fan Roy Thomas at the helm. At least Severin and Brodsky were good with editorial management.

Pg. 39: “Most of Marie’s army left Marvel to go on to other creative careers. It is not entirely surprising, given the limited creative parameters of what they were tasked with doing at companies like Marvel and DC. Others, like Irene, left because they refused to sign Marvel’s Loyalty Oath, which was essentially the first work-for-hire contract, transferring all art ownership to the company. Often, women left for better compensation.”

Pg. 40: “Many artists, seeing the popularity of Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix and his satirical take on the perception of artists, tried to emulate his mix of self- and societal loathing; they often ended up perpetuating the misogyny that permeated much of the content culture of the time- and in the process, alienating many of the women who had come West seeking a new creative vehicle.”

“Said Trina Robbins in Roger Sabin’s Comics, Comix, & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art, “It’s weird to me how willing people are to overlook the hideous darkness in Crumb’s work… what the hell is funny about rape and murder?”

THANK you, Ms. Robbins. I included this passage especially because of my recent article on Crumb and the consistent erasure and rationalization from White liberal art hipsters to excuse his work as some sort of subtle commentary.

Pg. 54: “When I came in, they thought the comics industry was over. There were jobs to be had, but there was no money with which to be paid for them. The only reason anyone was getting into comics was for love of the medium.” – Jo Duffy

And that is relatable- passion is important. But it’s the same today with comics journalism and comics criticism– except, I believe the people working in it should stop incessantly reminding their audiences how little money they make and lamenting about it publicly. It disrupts the experience of actually reading and enjoying said comics journalism.

“One time, Will Eisner asked me, “What makes you think you can do this?” And I said, “Because I’m doing it! I like it, and I’m good at it!” It was the only time I spent with Will Eisner, and there he was, studying me as an anomaly. It was really funny. He was a lovely man and a phenomenal creator, but he just couldn’t get his brain around the fact that I, a woman, wanted to do this and could. And yet there was nothing wrong with me.” – Jo Duffy

Again, Will Eisner always gets a pass because the comics industry itself needed figureheads for validation and credibility. Never forget it.

Pg. 56: “But this was a time where artists like Todd McFarlane were coming in with this specific style of extremely muscled, powerful male figures, which ended up taking over the industry to a certain degree in the nineties. And I think that the rise of the male sensibility in comics did some damage.” – Trina Robbins

Pg. 60: “But he [Editor] wouldn’t take no for an answer, so I ended up going home with the one-page script, and had a week to turn in twenty-one pages of art.” – Paty Cockrum

Even in 1984-1986, the Marvel Method was still going strong where a last-minute replacement artist, given the assignment with short notice, had to turn one page into twenty-one pages– and not be credited for writing. Stan’s legacy!

Pg. 74: “It’s not an easy way to make a living. It’s a fun way of making a living, if you love doing it. It’s not for the faint of heart. But I love it.” – Louise Simonson

Pg. 92: “If Chris Claremont was conjuring an X-Men: The Animated Series dream, he didn’t get there without Weezie and Annie, Margaret, Julia, and Stephanie. Or, for that matter, without Jean Grey, Storm, Rogue, or Jubilee.”

Pg. 114: “This was an industry-wide issue, to be sure. For the last twenty years, the success of comics and comic shops had been measured in single-issue periodicals largely made by and targeted to straight white men. Why, then, would a marginalized creator who could write or draw even think about wanting to work in comics? The atmosphere sometimes felt less than welcoming.”

Pg.115: “In terms of making comics, it’s always been about finding the audience and then delivering what that audience wants. And it’s so important having a story about a woman that you can read, said Bobbie Chase, editor in chief of the Marvel Edge imprint in 1994, and later the vice president of talent development at DC Comics.

“I believe that everyone wants a book they can read that looks like them or that feels like them or has the same experience as them,” she continued.

What they needed was a catalyst, and in 2012 they got it, in the form of three stars aligning: Kelly Sue DeConnick, Captain Marvel, and the Carol Corps.”

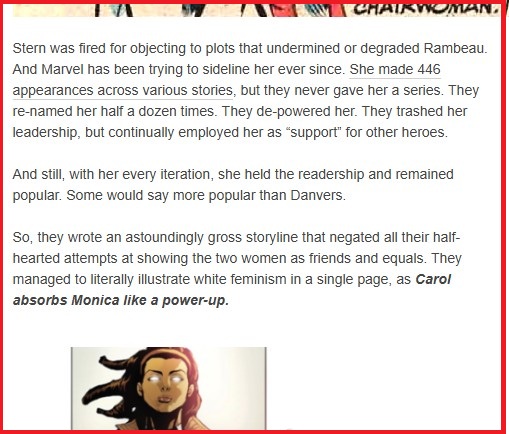

Here’s where I have a minor issue with this narrative- not that it’s for me to have an issue of any size with it, but- I still resent how the Black Captain Marvel, Monica Rambeau, is overlooked and shuffled aside- even by the authors of this book about female empowerment, representation and identification.

We’ve covered the racist and sexist- and deliberate- robbery of the first female Captain Marvel HERE.

The fact that it still goes undiscussed and isn’t a bigger deal- and that Monica Rambeau literally had her title, rank and identity taken from her and given to a bland white woman (!) and that isn’t a BIGGER DEAL- it amazes me, really. I recognize it wasn’t their doing in 1988 that did this, but their lack of care or attention to this is truly galling.

The authors seem to not feel as strongly as I do, because they cover Monica Rambeau very briefly, incorrectly, and even mistakenly refer to her as “Carol” when they should have put “Monica”. But it’s obvious what their agenda was, and it was to write a flattering and gushing PR essay about the glorification of Carol Danvers as much as possible, which is evidenced in the copious coverage of that specific character over anyone else, even other females with longer publication tenures or more iconic ones like Storm of the X-Men, for example.

I’ve often wondered why the Monica Rambeau situation- both with what Marvel editors did to her initially and then the replacement by Carol Danvers- ISN’T A BIGGER DEAL, especially with how wonderfully inclusive fandom and comic readers have grown over the years. But I’m especially amazed that three women working together (!) dishonored the character in such a dismissive way.

Here’s some thoughts from the tumblr BOSSUARY that shows someone else who feels strongly about this:

I was unaware of the scene that post describes where Carol absorbs Monica but- that’s really horrible and tone deaf. And I understand if the authors don’t know the history of what was done to this character- but, honestly- wasn’t it their job here to know?

Pg. 116: “Kelly Sue has that incredible quote that I’ve always wished was my own,” said Kelly Thompson, who took over duties as writer of the Captain Marvel ongoing comics series as of January 2019, after a two-year run by author Margaret Stohl, “Something like, ‘Captain America gets up because it’s right thing to do, but Carol Danvers gets up because f*** you.”

I agree that’s a great quote. By the same token, Monica Rambeau got up first. I guess Carol Danver’s white privilege gives her that attitude and Monica had to be happy being retconned into Carol’s sidekick in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Pg. 119: “She was a spin-off of a character who goes all the way back to the 1940s, the male version of Captain Marvel, also known as Mar-Vell, who was reconceptualized in the 1960s as a (Kree) alien who was sent to Earth as a spy, but fell in love with the people of his adopted planet.”

This is a sloppy and incorrect summary of Marvel’s Captain Marvel and I don’t want to outright blame the authors for being uninformed- I think maybe they just made a hasty error in trying to explain. The character of Mar-Vell does not go back to the 1940s; the authors seem to have been under the impression that the Fawcett Captain Marvel was connected to Marvel’s late 60s’ capitalization of the character’s name.

The proper way to have explained this would have been to point out that the Forties Captain Marvel has nothing to do with this character, so it cannot be a reconceptualization at all.

Pg. 121: “At the same time, Stan Lee was kicking around the idea of creating derivative female characters as a way to sell comics to more women (legend says there was a proto-version of She-Hulk on the board at the time) and who better to do it with than a character for whom they could extend their ability to retain a stamp on the Marvel name?”

The legend of a proto-version of She-Hulk is news to me unless the authors refer to Kenneth Johnson, producer of television’s The Incredible Hulk, and his- or the network’s intentions- to create a female version of the Hulk for a two-parter episode.

Of course, Jack Kirby had pitched a “She-Devil” character with a premise of repressed rage manifesting into a physical transformation, but the authors barely mention Kirby at all, so I have my doubts they’d even know about it. I’m positive Marvel knew about it.

We then get several pages of why Carol Danvers is such an interesting character, though she suffered through numerous reboots and identities (Binary, Warbird, Ms. Marvel), though the authors never point out that, as a derivative of an already bland male hero, she was never that compelling from the offset until her modern reboot.

Pg. 126: “In 1982, Monica Rambeau, a Black police lieutenant from New Orleans originally debuting in the pages of The Amazing Spider-Man, took on the mantle when she, like Carol, accidentally gained powers from an extra-dimensional energy source. Her journey with that code name ended violently, when she was stripped of her superpowers and the name so that Mar-Vell’s son could assume the role. Aside from a star turn in the cult favorite NextWave and until her return to the big screen in MCU’s Captain Marvel, Carol faded into relative obscurity.”

I have a lot to say about the above paragraph.

These authors are so eager to talk about Carol Danvers that they reduce a strong Black female character- that, again, had the title before Danvers- into a few throwaway sentences.

Those throwaway sentences are riddled with errors that are so lazy and so unprofessional that it’s almost as if Marvel still as an edict to continue depowering Monica Rambeau. This is, even unintentionally, White Supremacy continuing to creep into every facet of culture.

Yes, I am applying that term to a sloppily written and factually incorrect paragraph about fictional comic book characters– but it’s true.

“She was stripped of her superpowers and the name so that Mar-Vell’s son could assume the role”- this is 1000% false, but let’s say it was true- think about that sentence. THAT doesn’t provoke any sense of unfairness to these ladies? A Black woman pushed aside for a White guy’s SON? (Even if he’s an alien, he’s still a caucasian one!)

Monica was de-powered and leaves the Avengers in 1988. Genis-Vell is introduced half a decade later and doesn’t get a mini-series as ‘Captain Marvel’ until 1995.

You may criticize me as being extra nerdy here, but- if I can know this, WHY DON’T THEY?! They’re writing a book literally about invisible women and female characters that are underappreciated and underrepresented! So many mistakes just seems flippant- I wonder why this female Captain Marvel doesn’t get the same level of attention?

The ultimate insult is that final sentence. (Once again, this epic has THREE women working on it.) “Aside from a star turn in the cult favorite NextWave and until her return to the big screen in MCU’s Captain Marvel, CAROL faded into relative obscurity.” (emphasis mine) They even take Monica’s real name and put Carol’s in its place, accidentally. The ultimate insult and shoulder shrug towards a powerful Black female. The authors should be embarrassed about such an amateur mistake, at the least.

And please allow me to clarify something, if you’re at all perplexed as to why I am bringing up the Monica Rambeau character this much. It isn’t because I’m an uber-fan of any superhero character- I have not read NextWave, for example- it’s that when I initially stumbled across the true story of what Marvel Editors did to such a strong and progressive character I was both surprised and disgusted- and remain astonished that this story is still largely ignored and not a bigger deal.

There is something called Intersectional Feminism. I believe the three (White) writers did not display this whatsoever. Intersectional feminism says that you can’t fully understand sexism if you don’t consider race and class- there is no regard given for how a black character has been supplanted by a white one- and even, apparently, in modern stories I haven’t seen, absorbed by one. I don’t mean to offend anyone. But they focus completely on a white, blonde woman and give a middling paragraph- with factual errors- and even misname- to a Black woman. What else would it be?

Certainly, you couldn’t fault me for thinking it’d be a bigger deal amongst feminists. I have had to stress the injustice towards this character for context– both of the hypocrisy and rushed feel of some (not all) of the writing in this book.

Pg. 132: ” Part of that meant giving this new community a name. “Naming the Carol Corps was huge,” says Kelly Sue. “That was, probably next to marrying my husband, the smartest thing I ever did. And you know where that comes from, right? That came from the KISS Army.”

…because we know how progressive towards Women’s Rights the members of KISS have always been.

Pg. 143: “It’s easier for me to stick around because I’m a white woman. It’s a little easier for me than a woman of color, in part because all the heroes I get handed are white women. And I try to be the best ally I can. But until that room and until those stories are more diverse, we just still have a really long way to go.” – Kelly Thompson

Pg. 163: “In 2015, Emerald City Comic Con became the first major convention to offer all-gender restrooms in addition to women’s and men’s rooms, and after they saw lines as long as any other, in the years since have greatly expanded the number of them, with other conventions following suit.”

Pg. 173: “It is a struggle to know how to talk about harassment of women in the comics industry while still encouraging women to join it.”

The fact that ComicsGate fucks still have the time and inclination to insult and ridicule women in comics- from Gail Simone to Heidi MacDonald- is shameful, and I’d think as much as “the community” pats itself on the back about its gloriousness and hive-mind outlook, they’d want to be more proactive in combating this.

Pg. 177: “There is nothing inherently masculine about heroism.” – Kelly Sue DeConnick

Pg. 183: “I had no idea that I was the first Black nonbinary person to work both at Marvel and DC. I’m the first person. In 2021”, marveled Vita Ayala.

Pg. 205: “Emily Shaw, an associated editor who helped a new iteration of Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, left to pursue her master’s degree in business administration, and now works as a product manager at Netflix.”

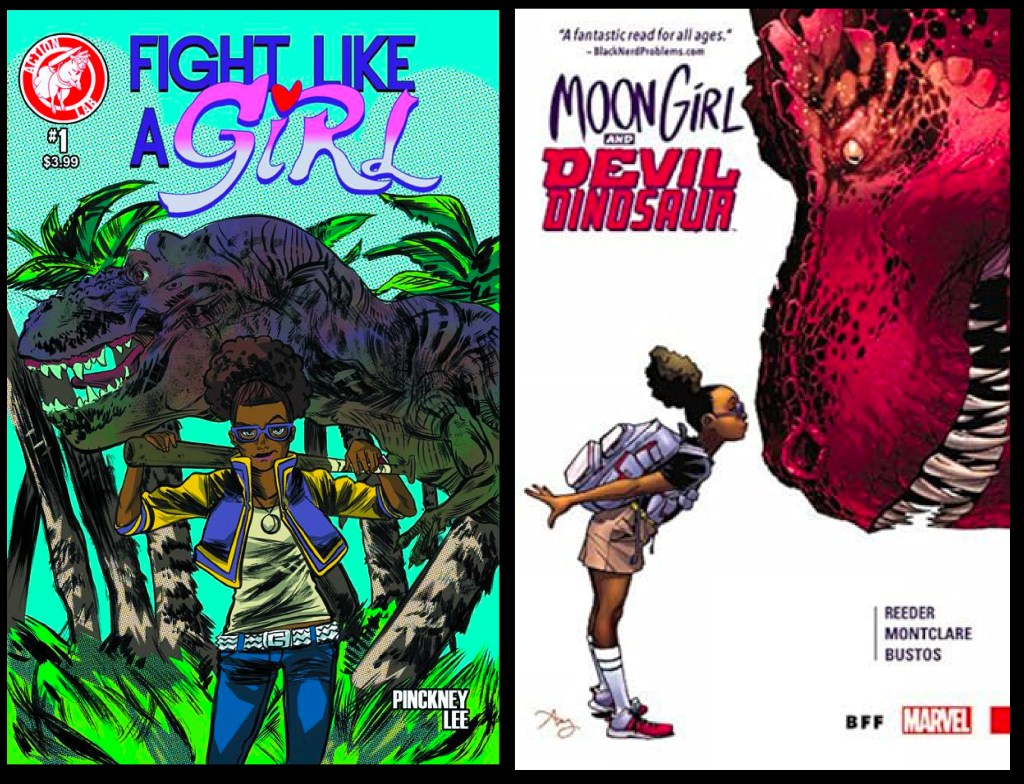

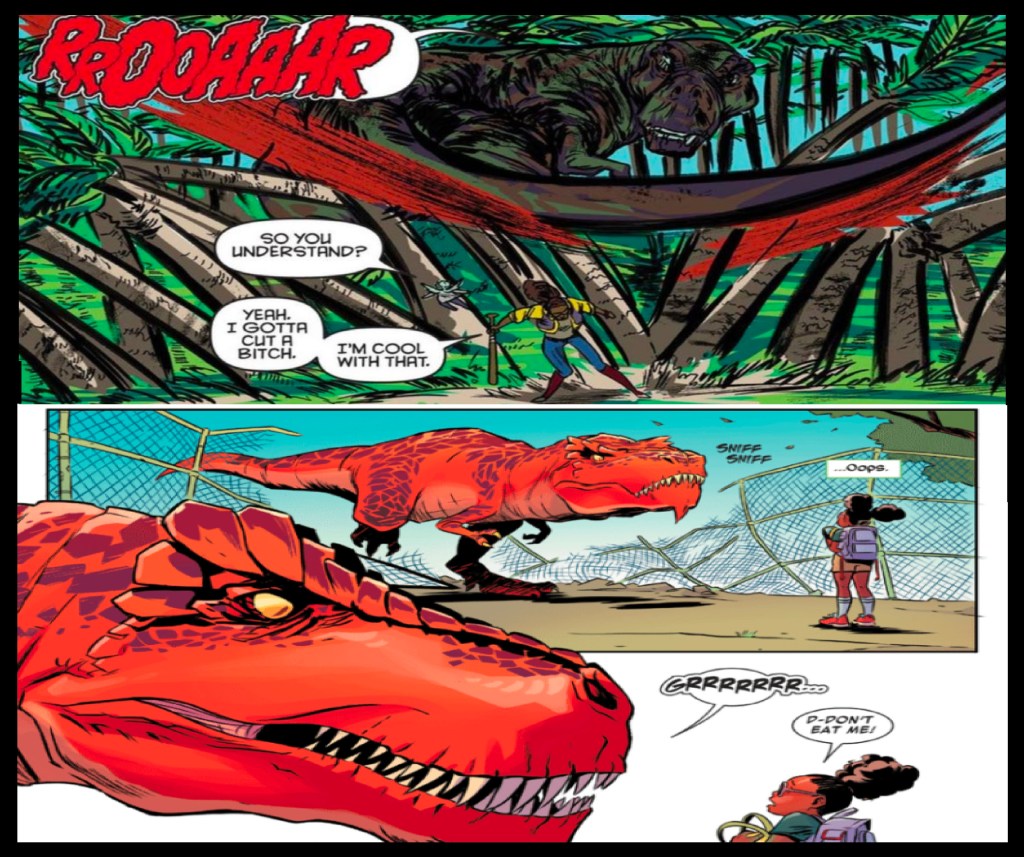

I find it interesting that Emily Shaw is credited as developing a new iteration of Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur– even this is a misnomer, in that there wasn’t an old iteration- Devil Dinosaur was a 70s’ Kirby series that had a Moon Boy– therefore, the duo of Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur didn’t exactly exist previously, so this would just be a new premise based on an old idea- but, as I noticed at the time, Marvel- and Emily Shaw, it seems- completely ripped off the visual look for an independent series that came out in 2014, drawn by the artist Soo Lee.

Months later, in 2015, Marvel premiered the Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur comic, and- well. It struck many as being directly ripped off on Lee’s visually designed female protagonist, who is depicted with a giant purple dinosaur. Compare and contrast and you tell me. (Soo Lee has never spoken on this matter that I am aware of and I did not contact her for this article.)

Ol’ Marvel, whether the “developers” are women or men, they are still strip-mining other concepts for their own intellectual property. This is one thing at least that seems to happen regardless of gender unfortunately.

Pg. 217: “And at the end of the day, you never know what’s going to inspire another person.” – Angélique Roché

Pg. 231: “We know Marvel was meant to be “the world outside your window,” as Stan Lee liked to say…”

There is no known quote that we can attribute to Stan Lee for saying that phrase. Naturally, he did talk about Marvel’s characters existing in the “real world”, but the only quotes found with this is Kevin Feige, and then Marvel Editor C.B. Cebulski stating that Stan Lee used to say it. (I know, I know, it’s minor but i had to touch on this.)

There’s several quotes and paragraphs strewn throughout that have nothing to do with the women behind Marvel, but do go to great lengths to reinforce that Marvel is “modern mythmaking and “eternal stories”, as well as literally dozens of asides about Stan Lee’s genius that makes me think this Marvel-sanctioned book had some sort of minor oversight over it. Or the authors are just very keen not to irk them in any way. I could be wrong, but sometimes it doesn’t connect to what has already been established in the narrative. Perhaps I just can’t read- it’s possible!

Pg. 235: “The suitability for a boy versus a girl simply did not enter my mind,” said Irene Vartanoff of the comics from the sixties that she remembers reading growing up. “If you read the house ads at the time, they would say boys and girls. They expected girls would read comics.”

Such a great quote and entirely correct!

Pg. 238: “She (Carol Kalish) also created Marvel Masterworks, a publishing program that reprinted, with restored art, out-of-print Marvel classics in a collectible format. “That’s a program that’s still going thirty years later,” says Sven Larsen, vice president of licensed publishing at Marvel, who worked under Carol in sales. “At that time, that material had never really been collected in any sort of permanent format. She was very forward-thinking that way in terms of what type of product the direct market would support.”

I actually did know a lot about Carol Kalish and have read what interviews she gave, and I had no idea she spearheaded and instigated Marvel’s extremely profitable Marvel Masterworks collected edition program.

Pg. 239: “Pat Redding, a Marvel editor and inker in the 1980s, remembers going into a shop that sold comics as a young girl and seeing Black Canary for the first time, drawn in fishnet stockings. “It always bothered me because all the men in comics were fat and old and bald,” she said. “And their wives were really shapely and always had dresses and high heels on and perfect hair when they were vacuuming or whatever. And I said, ‘Mom, why do they look that way?’ And she just said, ‘Oh, that’s an example of male chauvinism.”

Pg. 244: “Though it was her dream job, there was the necessary realignment of the fantasy of the job versus the day-to-day realities. Marvel is notorious for operating as lean as possible, which is how they’re able to innovate and execute ideas so quickly.”

(Huh?! Do they think giving creative people more resources and assistance somehow slows down the trajectory of getting stories out?)

“I hope we’re doing Stan and Flo justice.” – Adri Cowan

I know what they meant by this quote- Stan Lee and Flo Steinberg’s ability to communicate with fans in the Silver Age with a personable, sincere tone- but I do find it ironic that Flo Steinberg had to quit because she couldn’t get a five dollar raise. Stan Lee gave himself extra money on a weekly basis but didn’t see the value in Fabulous Flo. Never forget!

There’s a compelling and comprehensive history of the ‘Women of Marvel’ panel that eventually begat the podcast of the same name and makes valid points about how female creators understandably had an interest in appearing in other, non gender-centric panels at comic conventions- and did- but still met female fans that expressed gratitude that those panels that brought women editors, writers, and artists together existed.

Pg. 298: “Marvel’s Typhoid Mary, the Daredevil villain created by Annie Nocenti and John Romita Jr. in 1988, was named after Mary Mallon, the first known asymptomatic carrier of typhoid in the United States during the early 1900s, who unknowingly infected over a hundred people with typhoid fever and was subsequently kept in solitary confinement for thirty years. Alternately Matt Murdock’s lover and mortal enemy, Typhoid Mary is the answer to the question of what would happen if we turned the camera lens and followed the woman who was hurt in the process of advancing the male hero’s story.”

Another reason I suspect that Marvel loomed large in the preparation and writing of this book is the need to preface the character with ‘Marvel’s’, as if readers would be unaware Typhoid Mary was not ‘Marvel’s Typhoid Mary’ in a book where “Women of Marvel” is literally part of the title. But I might be overthinking, dear readers. Then again, it’s a very corporate thing to add ‘Marvel’s’ before a character’s name, is it not?

I still think Nocenti is a great, great writer and I was reading her Daredevil run in real time as a young child. The reason for this? The 7-11 in Delaware had a limited handful of comics and I took anything I could get relatives to buy me. I remember the Inferno storyline, Typhoid Mary dropping Daredevil off a bridge, (and I remember being unnerved that that story ended silently, with no “to be continued…” or anything) and all sorts of surreal things clearly not aimed at an eight-year-old child- but I enjoyed it all.

Pg. 300: “My heart was in this,” said Irene Vartanoff, “and I could break my heart in this business because of it. Because it’s human nature to clench to this thing, to make it part of you. To come into something that you care about is to leave yourself open to tremendous disillusionment.” – Irene Vartanoff

“Christiana Strain put it more bluntly: ‘Comics will never love you back.'”

Pg. 308: “I think comic fans, men specifically, are learning that when female characters get commended into the hands of women, women are going to get their experiences in there in ways that will make them unfamiliar with men,” said Tini Howard, Excalibur and Knights of X writer. “And I think the same can absolutely be said of Black characters, of queer characters, of disabled characters. If you are creating a character in a shared world that has something about them that you want to represent on the page, but maybe aren’t personally, isn’t part of your life personally, you have to accept that when other people get a hold of that, they’re going to explore that.”

Pg. 328: “There’s a type of power you’re afforded when you are not the only person in the room. And also that’s something we try to do. Leah and I are white women. There are times where we try to speak up for a Vita as a Black person or a nonbinary person or a Hispanic person, [and] there are times where we know that we can use the power we have all together for something that, maybe Vita is the only person in the room and doesn’t have to be. We can be the voice in the room with them.”

This. Preach! I am a big believer and practitioner that, if you’re white working in a diverse workforce, you can and should use your white privilege- it’s a thing, trust me- and be an advocate for other workers who are understandably less inclined to speak up. I speak up a lot- it’s not just here- and I tell my co-workers of color, “Let me do it, let them be annoyed with me instead”- and the success rate in doing so, unfortunately, is quite high. But the reality is that this still has to be done and more white people need to be the bridge to confront indoctrinated biases.

Pg. 359: “Marvel is where popular culture so often finds our parables and our lessons. Marvel is at the forefront of teaching our young people how to be.”

It isn’t for me to say what young people are inspired by- and I hope they are, and continue to be, inspired- but with the moral rot behind Marvel’s output, I’m a bit wary of glorifying the empire in the way stated above. Though, I don’t blame working writers for not wanting to burn bridges either.

All in all, this book has much to appreciate and again, is rich with illustrations and photographs that are invaluable. There was one notable absence in this book, and I am reluctant to mention it only because I sincerely do not want to seem self-referencing or self-glorifying in any way due to my interview with her last year- but where was Clair Noto?

Seriously- if Monica Rambeau is the invisible and forgotten character, then Clair Noto is the invisible and forgotten creator. Who was as marginalized, stolen from, and then forgotten by pros and fandom alike for literal decades? If I could locate Clair, then so too could these three people. After all, they had the support of Mighty Marvel behind them and, presumably, more resources than I did. It’s a curious omission, honestly.

That’s all for now, o voracious readers. Please remember that rampant sexism and toxic masculinity are still an ever-present and increasing danger- even now, in the 21st century. Please support equality and the respect of women. Thank you.

With my thanks to The Woman of Marvel, whether they enjoy this review or not- I’m betting on “not”- and J.L. and V.A. for some quick and important corrections! I’d like to leave you with a suggestion to all readers to consider donating to the Women and Girls Fund via TheLifeYouCanSave.org, which does so much for young women in poverty. Thank you!

Great piece!

One quick point: You noted, “Here’s some thoughts from the tumblr evilcyclopsxmen that shows someone else who feels strongly about this…”

I can’t tell if you’re arguing that “evilcyclopsxmen” stated this (in other words, they are the “someone else”) or if you meant that they reshared it from the initial poster “Bossuary”. Here’s their piece: https://bossuary.tumblr.com/post/177350677990/full-offense-monica-rambeau-deserved-to-be-the/amp (I should add that I’m not great with Tumblr so I’m hoping I’m correctly attributing this to Bossuary and not misunderstanding).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ah! Thank you, Von! I have never had a tumblr so didn’t recognize any of that. I must say, I was glad to see Bossuary’s statement(s). I will fix that now! Thanks again man.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m also disappointed they didn’t interview JayJay Jackson.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Absolutely. She should have been. Ditto for Clair Noto, as you noted.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Irene Vartanoff’s comment about the ads in 1960s comics being addressed to both boys and girls is less true of Marvel than other publishers, I think. In 2020, I wrote a blog post titled “Marvel Comics and the Male Gaze” about how the readers of the Bullpen Bulletins were assumed to be male: https://robimes.blogspot.com/2020/08/marvel-comics-and-male-gaze.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Rob, I took Irene’s statement to mean that she refers to comic books in general of the Sixties, not specifically Silver Age Marvel.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The first proto-She-Hulk appeared on the Benny Hill Show.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure it’s a prototype Mark, as it appeared on Benny Hill in 1981, whereas the Marvel She-Hulk appeared in Savage She-Hulk #1 which has a cover date of November 1979.

LikeLike

Wow. I had no idea about any of that drama with Monica… a character I fell in love with thanks to WandaVision, where she was portrayed brilliantly by the talented Teyonah Parris! Thank you for charting this, I do get a sense of these writers brushing over her because they were in a rush to to talk about the Carol CM.

All this has done is made me want to ignore this book when I see it in my public library and now go find comics that Monica shined in. Adding to my wish list now!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for the kind words. I would suggest reading that Avengers run by Roger Stern, John Buscema, and Tom Palmer which has Monica eventually growing into the role of leader of the Avengers. It’s never forced (like I feel the sudden importance of Carol Danvers was) and flows organically. For mainstream stuff, I feel Stern’s work holds up.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Another banger! I wasn’t aware of this book, and it’s unlikely to make my reading list now that I know about it, but I’m glad it’s been written, and I’m grateful for your review.

As someone who has taken too many deep dives into the Kirby/Lee debates, and seen the evidence of Stan Lee compulsively turning strong Kirby females into pathetic shrinking violets, it’s difficult to stomach the suggestions that Stan Lee had the vaguest of feminist sensibilities, or even the a cynical urge to cultivate female readers. I think it was Lee’s sexism that was part of the reason that Marvel didn’t become the top selling comics publisher until much later than most people assume. Marvel owned the 8-14 y/o superhero-loving (white) boy market, but didn’t even try to offer anything to anyone else.

On that note, of course you’re correct about the origins of She-Hulk. The story as I understand it is that Stan Lee/Marvel learned of Kenneth Johnson’s plan to add a She-Hulk to the TV show, and knew that the network could then spin her off into her own series (see The Six=Million Dollar Man —> The Bionic Woman) without paying Marvel a licensing fee. So Lee threw together a laughably lame version of She-Hulk and rushed it into production to claim the trademark. It was really the same MO as Marvel Comics’ taking over the Captain Marvel title in 1967: a pure trademark grab and nothing more. Ironically, that Lee/Colan version of Captain Marvel (i.e., Mar-Vell) was so slapdash and incoherent that it quickly failed despite considerable hype. It had to remain a published comic book title in order to hold onto the trademark, so Roy Thomas and Gil Kane again revamped the zombie Captain, and this time he failed even faster. Put another way, the origins of Marvel’s Captain Marvel is exhibit A in both Stan Lee’s and Roy Thomas’s incompetency in creating original superheroes.

The Cat was the first (possibly the only?) comic book for which I owned the complete run. As a young collector, frustrated that I had no chance to complete my Spider-Man or Daredevil collections in those pre-comic shop days, I jumped at the chance to buy all four issues a couple of years after they’d been published. I think they cost me a buck or two. I remember thinking that the character wasn’t any great shakes, but that it was at least as good as other characters that Marvel seemed intent on keeping in print. Even as a kid I could see that Marvel had missed the chance to comment on the then-prominent Women’s Movement, and explore some interesting male-female and female-female relationships. All the talk of Stan Lee and Marvel supposedly being in touch with youth culture and the zeitgeist were pretty much dispelled in just those few issues. Later I’ve read some accounts from some of the women who worked on those issues, and it’s evident that The Cat was the very definition of half-hearted. The shame is that some of those creators really wanted to try to do something new and interesting and relatable, but apparently weren’t given the chance.

LikeLiked by 2 people

honestly if you hadnt pointed it out about them giving an african-american character a short shrift and even messing up basic facts about why she had the Capt Marvel title removed i wouldnt have believed it. i dont see how this isnt damning for the rest of anything they state even though i was pleased to see the Carol Corps and more females getting into it. the authors need to give a public apology over this

LikeLiked by 3 people

BILL EVERETT took over from Steve Ditko on DR. STRANGE.

He did 6 episodes, before Marie Severin took over from him, and did 8 episodes.

Then Dan Adkins did 10 episodes, the last 2 full-lengthers.

Tom Palmer did 1 episode (inked by Adkins), before Gene Colan & Tom Palmer became a team and did 11 issues in a row.

How much (or how little) Roy Thomas did is increasingly in dispute these days. My impression is that Thomas promoted the idea that Adkins was criticized by fans for doing numerous Ditko swipes, but, really, I suspect he just said that because HE wanted to get paid for writing instead of Adkins. Adkins having been credited AND PAID for writing bucked the system. Adkins apparently thrw up his hands and just decided, OKAY, WHAT THE HELL, it’s easier to just ink and get paid for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Adkins also notably swiped from Johnny Craig and Jack Gaughan. Regardless of Thomas’ statements, Adkins was indeed guilty of massive swipery.

Not only that, but back in 1962 Adkins’ short career in SF digest illustration was terminated due to him being caught blatantly swiping from Frazetta.

Even worse, Adkins actually defended this practice in a 1971 Comics Crusader and said a comics career wasn’t possible without it. Gee, I guess Ditko, Kirby, Steranko, Wood, et al never got the memo…

LikeLike

Wood didn’t get the memo? Wallace “Never draw anything you can copy, never copy anything you can trace, never trace anything you can cut out and paste up” Wood?

LikeLike

You pulled this on another post here that was about a woman creator. Can you for once not try to sideswipe with snarky comments about credit thieves and swipe files? How about commenting on the subject for once?

LikeLike

Michael Hill? Is this a new pseudonym of yours?

LikeLike

Wood didn’t get the memo. Wallace “Never draw anything you can copy, never copy anything you can trace, never trace anything you can cut out and paste up” Wood?

LikeLike

Thanks for writing this. I read it nearly all the way through a month ago and then parked it until I could give the rest my attention (didn’t know I was so close to the end).

It’s disappointing to read about the treatment the character of Monica Rambeau received at the time as well as in the retelling by these authors. The spirit of Stan Lee lives on in this book, and I agree with Kevon, I’ve gotten as close to it as I want just by reading your review.

It never occurred to me to use a pseudonym and if my parents had been forward thinking enough to give me the middle name Ditko, I never would.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Adopting a pseudonym would probably be the best decision you could make if you’re ever foolish enough to publicly slime Irene Vartanoff by declaring her complicit in art theft again.

LikeLike

Did I say Vartanoff was complicit in the theft? No, but like Millie Shuriff and other Marvel employees, she was there. She knows what Thomas and Brodsky and Lee actually did to shit on Jack Kirby and steal his livelihood. She is contractually obligated to keep her mouth shut while her husband rationalizes shitting on Kirby in the ’70s, behaviour he passes off as just being one of a bunch of “ungrateful punks.” Attacking people who point out that there’s photographic proof that Vartanoff was at an event where thousands of pages of stolen original art were sold by representatives of the company that would later employ her can sadly be characterized as a reaction worthy of an attorney general, but it’s not a denial.

LikeLike

That has got to be the biggest load of Word Salad I’ve read from you yet.

Oh No! Irene Vartanoff attended a convention where swiped original art was being sold…AND SO DID EVERYBODY ELSE WHO ATTENDED IT. Boy, that’s one big conspiracy…

But, Irene Vartanoff MUST have known about this, of course. Why? Michael Hill Neurosis, as usual…

So when do we see your manifesto on Stan Goldberg’s repeated attempts to shit on Kirby by coloring him drably?

LikeLike